Western Supermajors in new scramble to tap Africa’s under-explored oil & gas resources

Ocean Rig Poseidon exploration vessel offshore Namibia

Africa has re-emerged on the radar of the major oil and gas explorers as the international supermajors – awash with cash following the recovery of crude oil prices – are once again targeting Africa’s potentially vast offshore and onshore hydrocarbon resource endowment.

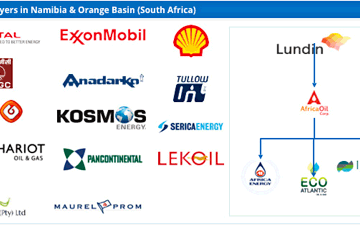

Some of the world’s biggest oil and gas explorers – from ExxonMobil to Royal Dutch Shell, and from British Petroleum to India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), are locating across the continent, as a new wave of asset acquisition and exploration gathers momentum.

Africa’s oil and gas industry is on track to double the number of wells sunk in the continent’s offshore and onshore prospects to more than 30 in 2018, up from the 17 sunk in 2017 – although this falls well short of the average 100 wells a year sunk between 2011 and 2014.

Rigs working in African waters are currently at a two-year high, according to data collected by Baker Hughes, one of the world’s largest oil field service providers, indicating that the continent may be on the cusp of another oil exploration boom to rival the post-millennium oil rush.

This is particularly good news for Southern Africa’s long-neglected hydrocarbons geography, which has hitherto yielded only marginal – mainly natural gas – discoveries.

Southern Africa to see spike in number of wells sunk

The region now faces the prospect of a spike in the number of exploratory wells sunk by the international supermajors, often with minors and even minnows as partners as the major players – many of whom failed to anticipate the world-class discoveries made along Africa’s eastern seaboard in Mozambique and Tanzania in 2010 – are desperate not to repeat the error.

The geology of Africa – especially the eastern, southern and western offshore and onshore prospects along the Southern African coastline and in the interior – remain largely unknown.

A regional comparison shows that more than 20,000 wells have been sunk in North Africa, a further 14,000 have been wells sunk in West Africa, and some 600 wells sunk in East Africa. But only a few dozen wells have been sunk in the entire Southern African region.

The mainstream oil and gas industry is lazy. It prefers to look for oil and gas in places where it has already been found. This helps to explain why more than a million wells have been sunk in Texas, but less than 30 have been sunk in Namibia. While this strategy greatly reduces the risk of sinking dry wells, it is not very useful in regions where the geology is largely unknown.

The US Geological Survey estimated in 2016 that there were 41 billion barrels of oil, and 319 trillion cubic feet of gas waiting to be found in sub-Saharan Africa. Given that Nigeria’s estimated reserves of oil alone currently stand at 36 billion barrels, and its reserves of natural gas are estimated at nearly 200 trillion cubic feet, the US estimates seem unduly conservative.

Over the last decade, more than 20 trillion square feet of natural gas has been discovered in East Africa in offshore Mozambique and Tanzania. New liquid hydrocarbons have been found in onshore Uganda and Kenya. In West Africa, new oil and gas discoveries have also been made in offshore Ghana, Ivory Coast and Senegal.

West Africa coastline seen as a ‘geological mirror’

Acquisitions along the West coast of Africa are seen particularly valuable by the industry as the region is seen as a geological mirror of the other side of the Atlantic, where huge discoveries have been made from Guyana to Brazil.

Seismological evidence supports this belief as West and Southwest Africa were once conjoined with Brazil before the supercontinent Pangea began to break up into individual continents some 200 million years ago. Consequently, West Africa and South America were once part of the same geological formation that gave rise to Brazil’s pre-salt Tupi field – the biggest offshore oil discovery in the Western hemisphere in three decades.

The supermajors have emerged leaner, meaner and cash-flow positive from the oil price downturn over much of the past four years, and competition is fast heating up for quality exploration acreage to rebuild reserves divested to offset debt during the slump.

With oil prices recovering to more than $70 a barrel in 2018, interest in Africa’s oil and gas potential has been reignited with the supermajors picking up exploration acreage abandoned by less cash-rich independents.

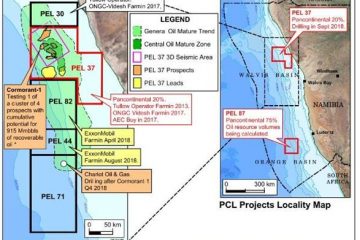

Last week London-listed Tullow Oil announced its decision to begin sinking an appraisal well in its Namibian offshore Cormorant-1 prospect located in Petroleum Exploration License 37 (PEL 37), some 420 kilometres south of the Angola-Namibia border. Tullow is exploring PEL 37 with partners ONGC Videsh, Canada’s Africa Energy, Namibia’s Paragon Investment Holdings, and Australia’s Pancontinental Oil & Gas.

The Tullow announcement came fresh on the heels of ExxonMobil’s decision to acquire stakes in two Namibian offshore fields from Portugal’s Galp in February, and from Southern Africa-focused minnow Azinam in August. It is unlikely to be the last

Africa New Energies’ concession extended

The transaction heralds increasing activity in offshore Namibia, and coincided with the government’s decision to extend the life of Africa New Energies (ANE) concessions in onshore Namibia along the border with Botswana. ANE’s strategy is to explore unfashionable geographies where the geology looks promising, using innovative exploration techniques to maximise its chances of success.

In October, French supermajor Total took a majority stake in Impact Oil’s offshore block in Namibia, along with an interest in South Africa’s offshore Orange River Basin. Shell secured its first exploration acreage in offshore Mauritania in July; Total continues to consolidate its position in Uganda, while BP is building up its Africa natural gas assets in Egypt, Mauritania and Senegal.

Total is exploring South Africa’s Mossel Bay; Shell is prospecting in the Orange River Basin, and Anadarko is exploring South Africa’s southwest offshore region in partnership with PetroSA – the state-owned oil and gas explorer.

Impact Oil is also exploring South Africa’s east coast, and in 2009 acquired four offshore blocks. After raising some $10 million to conduct seismic surveys, Impact sold 75% of its offshore interests to ExxonMobil, which is still smarting from missing Africa’s post-millennial oil rush.

Singapore-based Silver Wave Energy is exploring South Africa from Durban to the Mozambican border, hoping to replicate Eni of Italy and the Anadarko of the US’ discoveries in Mozambique’s offshore Rovuma Basin.

Australian explorers Kinetiko, Sunbird Energy and Magnum are prospecting South Africa’s onshore deposits, while Kalahari Energy, Tlou Energy and Magnum are focused on Botswana.

Exploration of Southern Africa’s oil & gas prospects were held back for decades as a result of the long-term impact of the 1980s anti-apartheid disinvestment campaign, and the delay flowing from the post-apartheid administration’s requirement for explorers to convert their old-order (apartheid era) mineral rights to new order (democratic era) mineral rights.

That process was completed in 2010, clearing the way for a new era of offshore and onshore exploration of the region’s long-neglected, and potentially bountiful hydrocarbons potential.

0 Comments